This blog is intended to be an outlet for research and questions on the textual criticism of the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible and related issues.

Thursday, May 17, 2012

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

University of Birmingham Postgraduate Conference Papers

The postgraduate papers have now been publicized for the University of Birmingham Postgraduate Conference on 6 June.

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

The Great Isaiah Scroll and Its Damaged Exemplar

In DJD 32, Ulrich and Flint make the case that the Great Isaiah Scroll does not reflect a later stage of development than the MT (contra Kutscher), but instead often reflects an earlier stage of development to which the MT adds significant insertions. They cite seven examples of "Insertions in M highlighted by 1QIsa(a)": 2:9b-10; 34:17-35:2; 37:5-7; 38:20b-22; 40:7; 40:14b-16; 63aβ-bα. In reading the Isaiah scroll recently, I believe I have noticed a pattern which would undermine the major pillars of their thesis.

Preliminarily, it should be admitted that it is quite possible that the Isaiah scroll preserves earlier, pre-expanded texts. 40:7 may be an example, as the original scribe omitted the verse entirely. The Old Greek also omits this verse. The verse is redundant with v. 8. It also disrupts the connection between vv. 6 and 8. Furthermore, the way v. 7 explicitly identifies the referents in the metaphor is characteristic of explanatory glosses. So v. 7 may be a late expansion in the MT. On the other hand, it may be a simple case of haplography in the Greek and Isaiah scroll.

That said, I have noticed a pattern, which may alternatively explain four (34:17-35:2; 37:5-7; 38:20b-22; and 40:14b-16) of Ulrich's and Flint's seven examples. First, none of these can be explained by homoioteleuton. Second, each of these verses are secondarily inserted into the manuscript, bringing the text into alignment with the MT. Third, the original scribe intentionally left one or more blank lines at each of these points, possibly indicating awareness of textual problems. And fourth, each of these four minuses occur at approximately the same location in their respective columns. Noting these patterns, I would like to propose an alternative explanation for these examples.

The four first-hand omissions in 1QIsa(a) at 34:17-35:2; 37:5-7; 38:20b-22; and 40:14b-16 do not reflect a pre-MT stage in the development of the text of Isaiah, but rather a damaged exemplar used by the original scribe of 1QIsa(a). Upon reaching the damaged edges, the scribe left blank spaces in his new copy to be filled in with the correct text from another manuscript at a later time and then continued with the first subsequent legible texts. It is unlikely that the original scribe would have known the expanded text of Isaiah well enough to note the absence of such innocuous additional texts and to note them while copying a non-expanded text (contra Ulrich and Flint). Rather, the consistent pattern of blank spaces and their consistent locations in the text indicate a defective exemplar, which the original scribe copied as best as he could, leaving blank lines for later insertion of the lacunae.

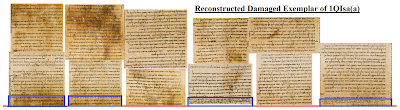

I have rearranged the columns in 1QIsa(a) from photographs on the Israel Museum website to approximate what this reconstructed exemplar must have looked like. The red base line indicates the bottom margin of the exemplar, and the blue boxes mark off the damaged portions of the text. This reconstruction can only be approximate, since 1QIsa(a)--and probably its exemplar--has uneven column widths, but it is sufficient to show that the physical reconstruction of the manuscript provides an obvious explanation for the minuses.

As we can see, all four of the major minuses occur at the bottom margin (potentially you could make the same case for the top margin) of the exemplar in close proximity. If the scroll had been damaged at that point, we would have a very straightforward explanation for how the verses could have been omitted in 1QIsa(a).

This proposal has several advantages of Ulrich's and Flint's proposal.

1) It does not require complex hypotheses about the scribe copying the non-expanded text while having in the back of his mind the expanded text, leaving room for (but not including) this alternative text. I would be interested to see if they can cite any other examples where this kind of procedure was followed. But I consider it quite unlikely that the scribe would have known both texts that well and followed such a scribal practice. My solution is much simpler and much more natural.

2) It explains why these "MT insertions" concentrate on such a small section of text, rather than being equally spread out across the entire book.

3) It explains why all of these were later inserted according to the MT, including one claimed by Ulrich and Flint to be in the original hand (37:5-7). Also interesting is the fact that (if their analysis is correct), the original scribe in 37:5-7 stopped mid-word, and then secondarily inserted the missing text! This would seem to be clear evidence for an exemplar whose bottom edge was defective.

For all of these reasons, my theory of a damaged exemplar for 1QIsa(a) seems to me to account for the evidence in a much simpler and more realistic manner than Ulrich's and Flint's proposal that it reflects a pre-MT stage of development. Careful attention to the physical characteristics of the manuscript and the practical mechanics of copying manuscripts has helped resolve several major textual problems. Without these central pillars, Ulrich's and Flint's theory is based on slender evidence indeed.

Update (10 April 2013): I have posted about the publication of my full DSD article on the Isaiah scroll here.

Preliminarily, it should be admitted that it is quite possible that the Isaiah scroll preserves earlier, pre-expanded texts. 40:7 may be an example, as the original scribe omitted the verse entirely. The Old Greek also omits this verse. The verse is redundant with v. 8. It also disrupts the connection between vv. 6 and 8. Furthermore, the way v. 7 explicitly identifies the referents in the metaphor is characteristic of explanatory glosses. So v. 7 may be a late expansion in the MT. On the other hand, it may be a simple case of haplography in the Greek and Isaiah scroll.

That said, I have noticed a pattern, which may alternatively explain four (34:17-35:2; 37:5-7; 38:20b-22; and 40:14b-16) of Ulrich's and Flint's seven examples. First, none of these can be explained by homoioteleuton. Second, each of these verses are secondarily inserted into the manuscript, bringing the text into alignment with the MT. Third, the original scribe intentionally left one or more blank lines at each of these points, possibly indicating awareness of textual problems. And fourth, each of these four minuses occur at approximately the same location in their respective columns. Noting these patterns, I would like to propose an alternative explanation for these examples.

The four first-hand omissions in 1QIsa(a) at 34:17-35:2; 37:5-7; 38:20b-22; and 40:14b-16 do not reflect a pre-MT stage in the development of the text of Isaiah, but rather a damaged exemplar used by the original scribe of 1QIsa(a). Upon reaching the damaged edges, the scribe left blank spaces in his new copy to be filled in with the correct text from another manuscript at a later time and then continued with the first subsequent legible texts. It is unlikely that the original scribe would have known the expanded text of Isaiah well enough to note the absence of such innocuous additional texts and to note them while copying a non-expanded text (contra Ulrich and Flint). Rather, the consistent pattern of blank spaces and their consistent locations in the text indicate a defective exemplar, which the original scribe copied as best as he could, leaving blank lines for later insertion of the lacunae.

I have rearranged the columns in 1QIsa(a) from photographs on the Israel Museum website to approximate what this reconstructed exemplar must have looked like. The red base line indicates the bottom margin of the exemplar, and the blue boxes mark off the damaged portions of the text. This reconstruction can only be approximate, since 1QIsa(a)--and probably its exemplar--has uneven column widths, but it is sufficient to show that the physical reconstruction of the manuscript provides an obvious explanation for the minuses.

As we can see, all four of the major minuses occur at the bottom margin (potentially you could make the same case for the top margin) of the exemplar in close proximity. If the scroll had been damaged at that point, we would have a very straightforward explanation for how the verses could have been omitted in 1QIsa(a).

This proposal has several advantages of Ulrich's and Flint's proposal.

1) It does not require complex hypotheses about the scribe copying the non-expanded text while having in the back of his mind the expanded text, leaving room for (but not including) this alternative text. I would be interested to see if they can cite any other examples where this kind of procedure was followed. But I consider it quite unlikely that the scribe would have known both texts that well and followed such a scribal practice. My solution is much simpler and much more natural.

2) It explains why these "MT insertions" concentrate on such a small section of text, rather than being equally spread out across the entire book.

3) It explains why all of these were later inserted according to the MT, including one claimed by Ulrich and Flint to be in the original hand (37:5-7). Also interesting is the fact that (if their analysis is correct), the original scribe in 37:5-7 stopped mid-word, and then secondarily inserted the missing text! This would seem to be clear evidence for an exemplar whose bottom edge was defective.

For all of these reasons, my theory of a damaged exemplar for 1QIsa(a) seems to me to account for the evidence in a much simpler and more realistic manner than Ulrich's and Flint's proposal that it reflects a pre-MT stage of development. Careful attention to the physical characteristics of the manuscript and the practical mechanics of copying manuscripts has helped resolve several major textual problems. Without these central pillars, Ulrich's and Flint's theory is based on slender evidence indeed.

Update (10 April 2013): I have posted about the publication of my full DSD article on the Isaiah scroll here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)